SOUTH AFRICA

(Updated 2021)

PREAMBLE AND SUMMARY

South Africa maintains two pressurized water reactors (PWRs) at the Koeberg nuclear power plant (NPP), commissioned in 1984 and 1985, respectively, which produced 6.7% of South Africa’s electricity in 2019 [1]. South Africa is anticipating building new large NPPs in the future. Koeberg is the only commercial nuclear power station in Africa.

This CNPP provides information on the status and development of nuclear power programmes in South Africa, including factors related to the effective planning, decision making and implementation of the nuclear power programme that together lead to safe and economical operations of NPPs.

It summarizes organizational and industrial aspects of nuclear power programmes and provides information about the relevant legislative, regulatory and international framework in South Africa.

1. COUNTRY ENERGY OVERVIEW

1.1. ENERGY INFORMATION

1.1.1. Energy policy

The Republic of South Africa has large coal deposits, small hydro potential and very small deposits of gas (exploration for natural gas on South Africa’s west coast is under way — indications of the presence of natural gas have not yet been quantified). South Africa also has large uranium deposits associated with its gold bearing ores. In addition, the country is endowed with renewable energy resources from solar and wind in coastal and mountainous areas, as well as huge opportunities for energy efficiency. South Africa’s indigenous energy resource base to date is still dominated by coal.

The energy sector is mainly guided by the following policies:

The White Paper on Energy Policy [2]: Promulgated in 1998, this white paper gives an overview of the South African energy sector’s contribution to gross domestic product (GDP), employment, taxes and the balance of payments. It concludes that the sector can contribute significantly to a successful and sustainable national growth and development strategy. The Energy Policy contains five key objectives, which form the foundation for South Africa’s energy policy: (i) increasing access to affordable energy services, (ii) improving energy governance, (iii) stimulating economic development, (iv) managing energy related environmental and health impacts, and (v) securing supply through diversity.

The White Paper on the Renewable Energy Policy [3]: Promulgated in 2003, this white paper outlines a long term vision of a sustainable, completely non-subsidized alternative to fossil fuels. The initial aim of 10 000 GWh of renewable energy contribution was to be achieved over ten years, mainly from biomass, wind, solar and small scale hydro.

The Nuclear Energy Policy [4]: Promulgated in 2008, this policy outlines the South African Government’s vision for the development of an extensive nuclear energy programme by ensuring that the prospecting and mining of uranium ore and the use of uranium (or other relevant nuclear materials) as a primary resource of energy is regulated and managed for only peaceful purposes.

The National Development Plan [5]: Published in November 2012, this plan outlines the 2030 vision for South Africa’s energy sector. In this plan, the energy sector will promote: (i) economic growth and development through adequate investment in energy infrastructure and the provision of quality energy services that are competitively priced, reliable and efficient, with local production of energy technologies supporting job creation; (ii) social equity through expanded access to energy services, with affordable tariffs and well targeted and sustainable subsidies for needy households; and (iii) environmental sustainability through efforts to reduce pollution and mitigate the effects of climate change.

The Integrated Resource Plan 2010–2030 [6]: Published in 2011, this plan provides a long term strategy for electricity generation spanning 2010–2030. It calls for a doubling of electricity capacity, using a diverse mixture of energy sources, mainly coal, gas, nuclear and renewables, including large scale hydro, to be imported from the southern African region. Implementation of the Integrated Resource Plan 2010–2030 is carried out through ministerial determinations, which are regulated by electricity regulations on new generation capacity. These are released periodically. Once released, the ministerial determinations signify the start of a procurement process and provide a greater level of certainty to investors.

The Integrated Resource Plan (IRP 2019) [7]: This was approved in October 2019 and stipulates 2500 MW capacity of nuclear power as part of the energy mix. It also recognized the extension of the design life and safety of the two unitsof the Koeberg NPP for an additional 20 years, until 2044 and 2045, respectively.

Energy efficiency

In 2005, the Government published a National Energy Efficiency Strategy [8], the aim of which was to provide for the coordinated implementation of an energy efficiency programme. The strategy also had set economy wide energy reduction of 12% by 2015, using 2000 as a base year. Inspired by the achievement of 21.4% economic wide energy consumption reduction by 2015, new sets of measures were developed under a new post-2015 strategy spanning 2015–2030 [9]. The new strategy explored new approaches to increase and encourage participation of other sectors that may have fallen behind during the implementation of the first phase of the structure.

In response to the publishing of the strategy, the Government initiated sector specific energy efficiency initiatives pursuant to the achievement of the set targets. Among the initiatives implemented were:

The industrial sector energy efficiency programme: The programme was aimed at creating the necessary enabling instruments to increase the uptake of energy efficiency investment in the industrial sector. Among these enabling instruments was the establishment of a training programme focusing on industrial systems optimization, the development and implementation of the energy management standard (SANS50001) [10] and the development and implementation of the measurement and verification standard (SANS50010) [11]. Operational managers and engineers were trained in the application of these standards across the country.

In the residential sector: The South African Government initiated energy efficiency standards and a labelling programme for appliances. The project aims to set measures necessary to overcome barriers impeding the widespread uptake and adoption of energy efficient appliances country wide. The project’s key focus and deliverables included:

Defining energy efficiency classes and minimum energy performance standards (MEPs);

Reviewing and implementing the policy and regulatory framework needed for a sustainable programme;

Strengthening the capacity of institutions involved in the implementation of the programme;

Developing and implementing market surveillance and compliance procedures;

Developing an appropriate awareness and communication campaign.

To this end, introducing mandatory energy efficiency requirements will be achieved through the introduction of compulsory MEPS as well as energy efficiency labels and standards. These specifications and standards are being enforced through regulations determined by the National Regulator for Compulsory Specifications (NRCS) in concurrence with the South African Bureau of Standards (SABS), the Department of Energy (DOE) and the Department of Trade and Industry (DTI). Successful implementation of this project will see the end of sales of inefficient appliances in the South African market. This project is also expected to influence consumer buying patterns towards more energy efficient appliances and equipment by raising awareness of their economic and environmental benefits.

Municipal energy efficiency and demand side management programme

Energy Efficiency and Demand Side Management (EEDSM) is an initiative funded by the Government through the Division of Revenue Act (DoRA) and is aimed at assisting selected municipalities with the implementation of energy efficiency technologies within the municipalities’ own energy consuming infrastructure in order to reduce electricity usage linked to that infrastructure. The measures considered for funding are currently limited to the retrofitting of energy efficient technologies for street, traffic and building lighting and the implementation of efficient technologies in both the wastewater treatment plants and freshwater pump stations. The measures are focused on improving the efficiency of electricity usage within the local government sector thereby minimizing supply interruptions.

The municipal programme forms part of the broader energy efficiency and demand side management programme led by the Government, the South African electricity utility Eskom and the business community, among others. The initiative would contribute significantly towards the national energy efficiency targets stipulated in the National Energy Efficiency Strategy (NEES). It is important for the Government from a policy perspective to continue leading the implementation of a clean energy programme country wide but also to understand the inherent challenges, including technology limitations, technology costing, and skill availability, limitations and requirements, and to continue with energy savings data collection in order to assess the impact against the business-as-usual scenario.

Municipalities are spending large amounts of revenue on purchasing energy to provide local public services such as street lighting, traffic signals, office lighting, water pumping and wastewater treatment facilities. Through cost effective actions, and the introduction of energy efficient measures and technologies, energy and monetary savings can be achieved in municipal operations. Improving the energy efficiency of the municipal infrastructure has far reaching benefits in that it provides the municipalities with the opportunity to reconfigure their operations, while reducing costs and improving service at the same time. Energy efficiency in the provision of local public services frees financial resources in the long run. Such resources could be used for the further provision of vital services. The budgets for these services often lack funds to invest in improvements. It is envisaged that through the clean energy programme, municipalities will reduce their electricity bills by optimizing energy use, improving delivery of services and reducing greenhouse gas emissions.

The new strategy will now have a 15 year (2016–2030) range with different sectoral targets. In addition to this, the DOE has released draft regulations [12], which will provide the data requirements for legal entities that use more than 400 terajoules (TJ) to develop energy management plans.

1.1.2. Estimated available energy

TABLE 1. ESTIMATED AVAILABLE ENERGY SOURCES

| Fossil fuels | Nuclear | Renewables | ||||

| Coal | Crude Oil | Natural Gas | Uranium** | Hydro | Other renewable | |

| Total amount in specific units* | ||||||

| Total amount in exajoules (EJ) | ||||||

* Solid, liquid: million tonnes; Gas: billion m3; Uranium: metric tonnes; Hydro, renewable: TW.

** Please note that uranium estimates do not make assumptions regarding recycling capabilities or a closed nuclear fuel cycle.

Source: IAEA/NEA Uranium ‘Red Book’, World Energy Council.

1.1.3. Energy consumption statistics

TABLE 2. ENERGY CONSUMPTION

| Final Energy consumption [PJ] | 2000 | 2005 | 2010 | 2015 | 2019 | Compound annual growth rate 2000–2019 (%) |

| Total | 2 263 | 2 546 | 2 645 | 2 788 | 2 803 | 1.13 |

| Coal, Lignate and Peat | 605 | 721 | 658 | 682 | 588 | -0.15 |

| Oil | 667 | 789 | 929 | 1 073 | 1 132 | 2.82 |

| Natural gas | 36 | 78 | 50 | 94 | 99 | 5.47 |

| Bioenergy and Waste | 329 | 263 | 277 | 247 | 246 | -1.52 |

| Electricity | 626 | 694 | 728 | 687 | 733 | 0.83 |

| Heat | 0 | 1 | 3 | 5 | 5 |

* Latest available data, please note that compound annual growth rate may not be representative of actual average growth.

** Total energy derived from primary and secondary generation sources. Figures do not reflect potential heat output that may result from electricity co-generation.

Source(s): United Nations Statistical Division, OECD/IEA and IAEA RDS-1.

1.2. THE ELECTRICITY SYSTEM

1.2.1. Electricity system and decision making process

Energy policy decision making is the responsibility of the Government. The National Energy Regulator of South Africa (NERSA) is a regulatory authority established by the National Energy Regulator Act of 2004 [13] to regulate the electricity, piped gas and petroleum pipeline industries in terms of the Electricity Regulation Act of 2006 (Act No. 4 of 2006) [14]; Gas Act of 2001 (Act No. 48 of 2001) [15] and Petroleum Pipelines Act of 2003 (Act No. 60 of 2003) [16], respectively.

The Electricity Regulation Act of 2006 [14] and its regulations enable the Minister of Mineral Resources and Energy (in consultation with the energy regulator, NERSA) to determine what new capacity is required. Through ministerial determinations, electricity capacity is procured (Eskom and independent power producers — IPPs) and added to the national grid (operated by Eskom) with electricity pricing regulated by NERSA. NERSA’s mandate to regulate the electricity, piped gas and petroleum pipeline industries is further derived from published Government policies as well as regulations issued by the Minister of Mineral Resources and Energy.

The South African electricity utility, Eskom, is mandated to provide electricity generation, transmission, and distribution and sales services in the country. Its customer base includes industrial, mining, commercial, agricultural, international, municipal and residential customers and redistributors.

1.2.2. Structure of the electric power sector

The South African electric power supply system consists of various generators including Eskom, municipalities, IPPs and private generators. Private generators (e.g. Industry and Mines) and municipalities generate electricity mostly for their own use. Eskom generates about 95% of the national electricity grid requirements. Eskom had a nominal capacity of 45 117 MW and the renewable energy IPPs had an installed capacity of 5 206 MW in 2020 [17]. The renewable energy IPPs sell their electricity to Eskom via power purchase agreements. Table 3a below provides a summary of installed capacities of Eskom and IPPs.

The electricity generated is transported through an Eskom owned network of high voltage transmission lines that connect the load centres. Eskom and municipalities distribute the electricity to various end users (residential, commercial, industry, mining, rail, agriculture and international).

1.2.3. Main indicators

TABLE 3. ELECTRICITY PRODUCTION

| Electricity production (GWh) | 2000 | 2005 | 2010 | 2015 | 2019 | Compound annual growth rate 2000–2019 (%) |

| Total | 210 670 | 244 922 | 259 601 | 249 655 | 252 223 | 0.95 |

| Coal, Lignate and Peat | 193 419 | 229 055 | 241 872 | 228 498 | 221 244 | 0.71 |

| Oil | 0 | 78 | 197 | 183 | 182 | |

| Natural gas | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Bioenergy and Waste | 307 | 285 | 332 | 372 | 443 | 1.95 |

| Hydro | 3 934 | 4 199 | 5 067 | 3 729 | 5 798 | 2.06 |

| Nuclear | 13 010 | 11 293 | 12 099 | 12 237 | 13 525 | 0.20 |

| Wind | 0 | 12 | 34 | 2 500 | 6 511 | |

| Solar | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 136 | 4 521 | |

| Geothermal | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

* Latest available data, please note that compound annual growth rate may not be representative of actual average growth.

** Electricity transmission losses are not deducted.

—: Data not available.

Source(s): United Nations Statistical Division, OECD/IEA and IAEA RDS-1.

TABLE 4. ENERGY RELATED RATIOS

| 2000 | 2005 | 2010 | 2015 | year* | |

| Nuclear/total electricity (%) |

*Latest available data.

Source: RDS-1 and RDS-2

—: data not available.

2. NUCLEAR POWER SITUATION

2.1. HISTORICAL DEVELOPMENT AND CURRENT ORGANIZATIONAL STRUCTURE

2.1.1. Overview

Construction of the Koeberg NPP began in 1976 and was undertaken by Framatome. The plant is owned and operated by Eskom and consists of two Framatome designed PWRs commissioned in 1984 and 1985, respectively. Koeberg produces 6.7% of South Africa’s electricity. It is the only commercial nuclear power station in Africa.

2.1.2. Current organizational structure

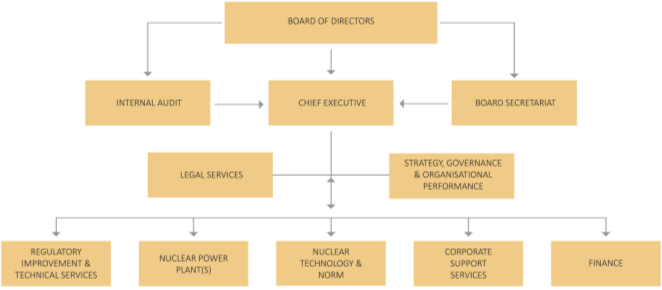

A simplified organizational chart of main operations in the nuclear power programme within South Africa is shown in Fig. 1.

FIG. 1. South Africa current organizational chart.

Detail is provided below on the mandate given to the organizations identified above within the South African nuclear programme.

The Nuclear Energy Act of 1999 [18] assigns responsibility to the Minister of Mineral Resources and Energy for the production of nuclear energy, the management of radioactive waste, as well as South Africa’s international commitments. The South African Nuclear Energy Corporation (Necsa) was established as a public company in terms of the Nuclear Energy Act, 1999 (Act No. 46 of 1999) [18] and is wholly owned by the State.

The National Nuclear Regulator (NNR) (previously the Council for Nuclear Safety — CNS) is the national authority responsible for exercising regulatory control over the safety of nuclear installations, radioactive waste, irradiated nuclear fuel, and the mining and processing of radioactive ores and minerals. The primary function of the NNR is to protect persons, property and the environment from the harmful effects (i.e. nuclear damage) arising from exposure to ionizing radiation. The NNR is an independent statutory organization whose powers are defined in the National Nuclear Regulator Act (Act No. 47 of 1999) [19]. The NNR is comprised of the board of directors appointed by the Minister of Mineral Resources and Energy. The board is responsible for management of the affairs of the regulator.

The National Radioactive Waste Disposal Institute (NRWDI) was established for the management of radioactive waste disposal on a national basis. The institute is an independent entity established by statute under the provision of section 55(2) of the Nuclear Energy Act (No. 46 of 1999) [18] to discharge this institutional obligation of the Minister of Mineral Resources and Energy. The National Radioactive Waste Disposal Institute Act (NRWDIA) (Act No. 53 of 2008) [20] endorsed the establishment of the NRWDI. The NRWDI has been listed as an independent national public entity, wholly owned by the State. The functions of the institute as per section 5 of the NRWDI Act (Act No. 53 of 2008) are summarized as follows:

Manage radioactive waste disposal on a national basis;

Operate the national low level waste disposal facility at Vaalputs;

Design and implement disposal solutions for all categories of radioactive waste;

Develop criteria for accepting and disposing of radioactive waste in compliance with applicable regulatory safety requirements and any other technical and operational requirements;

Assess and inspect the acceptability of radioactive waste for disposal and issue radioactive waste disposal certificates;

Manage, operate and monitor operational radioactive waste disposal facilities, including related predisposal management of radioactive waste on disposal sites.

2.2. NUCLEAR POWER PLANTS: OVERVIEW

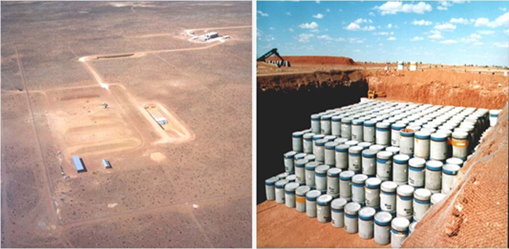

2.2.1. Status and performance of nuclear power plants

Eskom, the South African energy utility, owns and operates South Africa’s only nuclear plant, the twin reactor Koeberg power station near Cape Town, at the south-western tip of the country (see Fig. 2).

Source: ESKOM

FIG. 2. Koeberg nuclear power plant.

TABLE 5. STATUS AND PERFORMANCE OF NUCLEAR POWER PLANTS

| Reactor Unit | Type | Net Capacity [MW(e)] |

Status | Operator | Reactor Supplier |

Construction Date |

First Criticality Date |

First Grid Date |

Commercial Date |

Shutdown Date |

UCF for 2020 |

| KOEBERG-1 | PWR | 930 | Operational | ESKOM | FRAM | 7/1/1976 | 3/14/1984 | 4/4/1984 | 7/21/1984 | 94.6 | |

| KOEBERG-2 | PWR | 930 | Operational | ESKOM | FRAM | 7/1/1976 | 7/7/1985 | 7/25/1985 | 11/9/1985 | 78.9 |

| Data source: IAEA - Power Reactor Information System (PRIS). | |||||||||||

| Note: Table is completely generated from PRIS data to reflect the latest available information and may be more up to date than the text of the report. |

Source(s): IAEA PRIS Database.

Overall performance of the Koeberg nuclear power plant in 2019/2020

Koeberg Unit 1 was shut down for a refuelling and maintenance outage on 20 September 2019, and synchronized to the grid again on 6 January 2020. On 10 March 2020, the turbine was manually tripped after one of the main pumps in the seawater circulating cooling water system tripped; the secondary system cooling was inadequate due to a clogged heat exchanger. An automatic reactor scram was sustained while the turbine was being run down. The necessary repairs were made, and the unit returned to service on 14 March 2020. The unit remains online and is operating safely [17].

Unit 2 remained online since returning from a refuelling and maintenance outage on 26 December 2018. The next refuelling outage was planned to start at the end of April 2020, but this was delayed due to the national lockdown and international travel ban restricting required resources. Due to the reduced demand during the national lockdown, the unit was shut down on 4 April 2020. The unit was brought back to service on 11 July 2020; the two month refuelling outage commenced on 11 August 2020 [17].

In 2020 the two Koeberg units together delivered a net energy sent out of 13 252 GWh, compared with 11 580 GWh in 2019 [17].

2.2.2. Plant upgrading, plant life management and licence renewals

Koeberg NPP reaches its 40 year end of design life in 2024 and to ensure its continued operation going into the future, plans are already in place to extend its design life by another 20 years. A number of critical components have already been replaced as part of the plant’s life extension (e.g. refuelling water storage tanks). Work is currently in progress to replace the six steam generators (three for each unit). Work that is required to replace other components that will not make it for an additional 20 years or to the end of the plant’s original design life will be completed in the near future.

As part of the life extension project, Eskom is required to submit a safety case to the NNR in July 2022 to demonstrate that all the requirements as specified by the NNR are met and will be met during the long term operation of the plant.

2.2.3. Permanent shutdown and decommissioning process

Not applicable.

2.3. FUTURE DEVELOPMENT OF NUCLEAR POWER SECTOR

2.3.1. Nuclear power development strategy

The Nuclear Energy Policy (June 2008) [4] is guided by the White Paper on Energy Policy [2] as approved by the Government at the end of 1998, where it was retained as one of the policy options for electricity generation. As part of its national policy, the Government also encouraged a diversity of both supply sources and primary energy carriers. In terms of the white paper, the Government will investigate the long term contribution that nuclear power can make to the country’s energy economy and how the existing nuclear industrial infrastructure can be optimized. The Nuclear Energy Policy outlines the vision envisaged in the white paper. Some of the main policy objectives relate to decisions regarding possible new nuclear power stations, the management of radioactive waste, safety monitoring of the nuclear industry, effectiveness and adequacy of regulatory oversight, and a review of bodies associated with the nuclear industry.

Through the policy, the Government aims to achieve the following objectives:

Promoting nuclear energy as an important electricity supply option through the establishment of a national industrial capability for the design, manufacture and construction of nuclear energy systems;

Establishing the necessary governance structures for an extended nuclear energy programme;

Creating a framework for the safe and secure utilization of nuclear energy with minimal environmental impact;

Contributing to the country’s national programme of social and economic transformation, growth and development;

Guiding the actions to develop, promote, support, enhance, sustain and monitor the nuclear energy sector in South Africa;

Attaining global leadership and self-sufficiency in the nuclear energy sector in the long term;

Exercising control over unprocessed uranium ore for export purposes for the benefit of the South African economy;

Establishing mechanisms to ensure the availability of land (nuclear sites) for future nuclear power generation;

Allowing for the participation of public entities in the uranium value chain;

Promoting energy security for South Africa;

Improving the quality of life and supporting the advancement of science and technology;

Reducing greenhouse gas emissions;

Developing the skills related to nuclear energy.

South Africa is anticipating building new large NPPs of the Koeberg type in the future. The current approved electricity infrastructure development plan for the country is IRP 2019 [7]. It is based on a least-cost electricity supply and demand balance, taking into account security of supply and environment. It identifies the preferred generation technologies required to meet the expected demand growth up to 2030. Following the completion of IRP 2019 in October 2019, South Africa made a decision to commence preparations for a nuclear build programme to add 2 500 MW to the national electricity grid beyond 2030. Detailed information, such as number of units, location, type of contracts, etc, is not yet available as the programme is still in the very early stage.

The approved IRP 2019 advocates for Small Modular Reactors and as a result, South Africa is considering small modular high temperature gas cooled reactor technology based on the Pebble Bed Modular Reactor (PBMR) technology to determine whether this type of nuclear technology could be included in the energy supply system for the future.

2.3.2. Project management

Information regarding the planned nuclear build is not yet available.

2.3.3. Project funding

Information regarding the planned nuclear build is not yet available.

2.3.4. Electric grid development

Information regarding the planned nuclear build is not yet available.

2.3.5. Sites

In the mid-1970s, the Koeberg NPP consisting of two units with 1800 MW(e) capacity was built at Duynefontein site, 30 km north of Cape Town near Melkbosstrand on the west coast of South Africa. Both units entered operation in the mid-1980s.

In March 2016, Eskom as majority owner operator for NPPs submitted the Environmental Impact Review (EIR) to Department of Environmental Affairs (DEA) for Thyspunt (Eastern Cape) and Duynefontein (Western Cape) site for the 9.6 GW Nuclear New Build Programme. Following that, in October 2017 the Environmental Authorization (EA) was granted for the construction and operation of a NPP and associated infrastructure at Duynefontein. Subsequent to the EA being granted, appeals were lodged with DEA and these are still being addressed.

2.3.6. Public awareness

Public awareness of nuclear technology and energy is crucial and is one of the fundamental principles illustrated in the Nuclear Energy Policy of 2008 [4]. The Government has committed to create programmes to stimulate public awareness and inform the public about the nuclear energy programme. According to two studies performed by the Human Sciences Research Council on public perception of nuclear energy in 2011 [21] and 2013 [22], over 40% of the South African public does not know about nuclear technology and energy, and less than 20% of the public does not view it favourably. These studies were commissioned by the South African Nuclear Energy Corporation.

The country has since approved a Nuclear Communication Strategy in 2019 [23], which is developed and supported by various stakeholders in the sector. The strategy is designed so that it encourages close cooperation in implementing nuclear communication programmes to increase broader public reach as most of the communication has traditionally been done around the public residing within close proximity of nuclear installations (i.e. Gauteng (mainly Tshwane municipality) and Western Cape (Cape Town municipality)).

In the implementation of the governmental mandate and policy principle as contained in the Nuclear Energy Policy 2008, various partner organizations have been supported and partnered with, such as the South African Young Nuclear Professional Society and Women in Nuclear South Africa to mention a few. These partner organizations have helped the Government to actively drive the message to demystify nuclear technology and energy by sharing relevant information on its peaceful applications and career opportunities primarily in schools. At the international stage, South Africa remains fully represented by these partner organizations and this further helps to showcase the country’s activities and achievements.

The Department of Mineral Resources and Energy plans to ensure that a public survey is undertaken in the near future to further gauge the public’s perceptions of nuclear technology and energy. This will help further refine the nuclear communication strategy implementation.

The National Nuclear Regulator Act section 26(4) requires the holder of a nuclear installation licence to establish a Public Safety Information Forum (PSIF) to inform persons living in the relevant municipal area about an emergency plan, which has been established in terms of section 38(1) of the Act on nuclear safety and radiation safety matters related to the relevant nuclear installation.

The objective of the PSIF meetings is to make people aware of nuclear safety and protection matters and to give feedback reports on the activities of the nuclear installations and their potential hazards within the facility which could result in potential public exposure. The PSIF must conduct all meetings open to any member of the public at a minimum frequency of one meeting per quarter.

The PSIFs are held on a quarterly basis by Eskom, regarding the Koeberg NPP and Necsa, pertaining to the Pelindaba and Vaalputs sites respectively.

The nuclear installation licence holder invites the National Nuclear Regulator (NNR), the relevant municipality (Disaster Management Centre), the relevant Province (Disaster Management Centre) and relevant national Government departments as appropriate to all meetings to facilitate the sharing of information.

2.4. ORGANIZATIONS INVOLVED IN CONSTRUCTION OF NPPs

The DMRE is coordinating efforts on the new build programme, while Eskom is the designated owner operator for the nuclear entities. Different roles with respect to construction will still need to be defined once a procurement decision is affirmed. The intent is to formulate strategies that enable the local nuclear industry to support the new nuclear build programme and beyond.

2.5. ORGANIZATIONS INVOLVED IN OPERATION OF NPPs

The Koeberg NPP is owned, operated and maintained by Eskom Holdings SOC Ltd, a company established by the South African Companies Act. Maintenance and engineering support is provided by a number of original equipment manufacturers.

The South African Nuclear Energy Corporation (Necsa) was established as a public company by the Nuclear Energy Act, 1999 (Act No. 46 of 1999) [18] and is wholly owned by the State. The main functions of Necsa are to undertake and promote research and development in the fields of nuclear energy, radiation sciences and technology; to process source material, special nuclear material and restricted material; and to cooperate with persons in matters falling within these functions. Necsa provides technical expertise on nuclear technology, including expertise on uranium conversion and enrichment remaining from South Africa’s previous nuclear weapons programme.

Apart from its main operations at Pelindaba, including the SAFARI-1 research reactor, Necsa also operates on behalf of NRWDI the Vaalputs National Radioactive Waste Disposal Facility presently licensed to receive low and intermediate radioactive waste. This is mainly because Necsa is currently the holder of the Vaalputs nuclear installation licence, which according to the NNR requirements is not transferable. Necsa will continue to operate the Vaalputs repository until NRWDI has obtained its operating licence for the facility.

The National Nuclear Regulator oversees and regulates the safety of nuclear installations including NPPs through the lifecycle from design to decommissioning.

2.6. ORGANIZATIONS INVOLVED IN DECOMMISSIONING OF NPPs

In general, the financing for decommissioning and waste management follows the rule of ‘polluter pays’. In accordance with this principle, all holders of nuclear authorization are responsible for ensuring that sufficient resources are in place to meet their responsibilities with respect to decommissioning and radioactive waste management.

The safety standards and regulatory practices of the National Nuclear Regulator (Regulation R.388) [24], outlines the requirements that the nuclear installation licence holder must comply with when taking administrative and technical actions to remove all of the regulatory controls from a facility. The nuclear installation licence holder must submit the Decommissioning Strategy and Plan to the NNR for review. The owner-operator of NPPs must therefore demonstrate to the regulator that sufficient resources will be available from the time operation ceases to the termination of the period of responsibility.

Decommissioning and waste disposal are currently taking place in the following areas:

Low and intermediate level waste from Koeberg and Necsa’s Pelindaba site is disposed of in shallow landfill trenches at Vaalputs, the National Radioactive Waste Disposal Facility currently operated by Necsa on behalf of NRWDI and situated about 600 km north of Cape Town. Although the State financed the initial development costs of the site, Eskom and Necsa pay fees based on the amount of radioactive material sent to Vaalputs.

Decommissioning and associated waste management of Necsa’s two former enrichment plants as well as the former conversion plant and associated facilities are undertaken by Necsa itself and the financing is carried by the State through the annual State allocation for operational funds.

Decommissioning of disused mine equipment (primarily in the gold, copper, phosphate and mineral sands operations) is currently being undertaken. The mining companies finance the decommissioning costs themselves and subcontract the operations out to specialized agencies.

Financial provision for Koeberg decommissioning and spent fuel management has continued to be accumulated on a monthly basis since commercial operation of the installation began in 1984.

Management at Eskom and Necsa is responsible for determining the financial resources necessary to fulfil its legal responsibilities through the budgeting programme, including adequate funding for the management of spent fuel and the disposal of intermediate and low level waste. Similar arrangements are in place for the mines.

The Radioactive Waste Management Policy and Strategy [25] for the Republic of South Africa, makes provision for a national Radioactive Waste Management Fund that will be managed by the South African Government. Waste generators will contribute to the fund based on the radioactive waste classes and volumes produced. The fund is aimed at ensuring sufficient provision for the long term management of radioactive waste and includes the following:

Funding for disposal activities;

Funding for research and development activities, including investigations into waste management/disposal options;

Funding of capacity building initiatives for radioactive waste management;

Funding for other activities related to radioactive waste management.

Legislation for the establishment of a national radioactive waste management fund has been developed and is currently undergoing legal review by the State law adviser. In keeping with the polluter pays principle, the contributions to the fund will be from the generators of radioactive waste. The contributions shall be managed in an equitable manner, without cross-subsidization and be based on classification of the waste as well as the volume.

2.7. FUEL CYCLE INCLUDING WASTE MANAGEMENT

Fuel cycle

In late 1951, a South African company, Calcined Products (Pty) Ltd (Calprods), was formed with the objective of processing uranium rich slurries produced as a by-product of gold mining operations. In 1967 Calprods was replaced by the Nuclear Fuels Corporation of South Africa (Pty) Ltd (Nufcor), a private company. From 1967 to the present day, Nufcor’s head office’s main activities have included the marketing of uranium under long term contracts with international and local utilities (more recently, London based Nufcor International Ltd has assumed this marketing function) and the transporting of uranium products in accordance with international hazardous materials regulations.

Nufcor’s processing facility is located in Westonaria and its main activity is the processing of uranium rich slurries into uranium oxide powder. These slurries are collected from current producing mines owned by AngloGold and Palabora Mining Company.

Eskom is responsible for its own fuel procurement. Eskom procures conversion, enrichment and fuel element manufacturing services on the international market.

Waste management

The Radioactive Waste Management Policy and Strategy for the Republic of South Africa [25], published in November 2005, serves as the national commitment to address radioactive waste management in a coordinated and cooperative manner and represents a comprehensive radioactive waste governance framework by formulating, in addition to nuclear and other applicable legislation, a policy and implementation strategy in consultation with all stakeholders.

The Policy and Strategy outlines the main policy principles that South Africa will endeavour to implement through its institutions in order to achieve the overall policy objectives. It is founded on the belief that all nuclear resources in South Africa are a national asset and the heritage of its entire people, and should be managed and developed for the benefit of present and future generations in the country as a whole.

The scope of the Policy and Strategy relates to all radioactive waste and potential radioactive waste (including used fuel), except operational radioactive liquid and gaseous effluent discharges, which is permitted to be released to the environment routinely under the authority of the relevant regulators National Nuclear Regulator and the Directorate for Radiation Control (RADCON) under the Department of Health.

The Policy and Strategy makes provision for the establishment of two management structures for radioactive waste management: the National Committee on Radioactive Waste Management (NCRWM) and NRWDI.

The role of the NCRWM is to advise the minister and to oversee the effective implementation of the policy while the NRWDI is the implementing body with direct responsibility for siting, constructing and operating radioactive waste disposal and related facilities. The policy also calls for a National Radioactive Waste Management Fund to be established through the statutes in order to manage the radioactive waste disposal institute funds at a national level.

In accordance with the Policy and Strategy, final disposal is regarded as the ultimate step in the radioactive waste management process, although a stepwise waste management process is acceptable. Long term storage of certain types of waste (e.g. high level waste, long lived waste and spent sources) may be regarded as one of the steps in the management process.

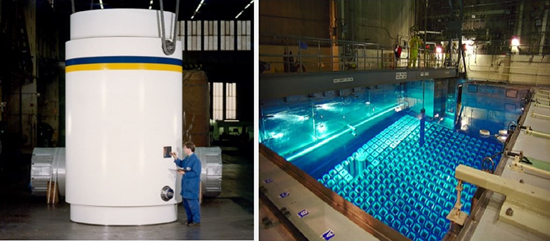

The Policy and Strategy prescribes the domain within which spent fuel shall be managed in South Africa. Spent nuclear fuel is currently stored in authorized facilities within the generator’s sites. Two mechanisms (i.e. dry and wet storage) are currently in use in South Africa.

The Policy and Strategy dictates that investigations shall be conducted to consider the various options for safe management of spent fuel and high level waste and states that the following options shall be investigated:

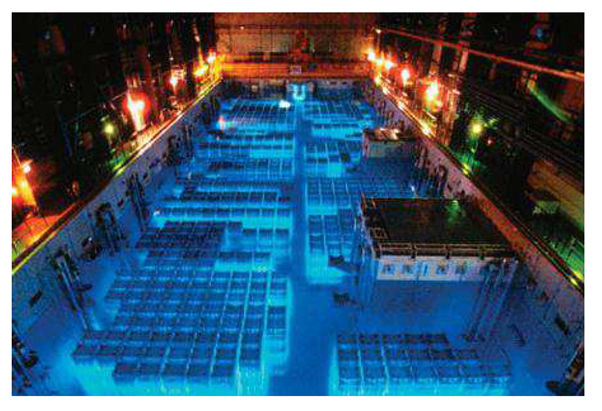

Low and intermediate level waste from Koeberg and Necsa is disposed of in metal drums and concrete containers, respectively, at the Vaalputs National Radioactive Waste Disposal Facility, some 600 km north of Cape Town, in near surface disposal trenches (see Fig. 3a). Vaalputs is currently operated by Necsa, on behalf of the NRWDI, until the Vaalputs nuclear installation licence is issued to NRWDI after it demonstrates to the NNR that it has the capacity and the resources to maintain the licence to the satisfaction of the NNR. The NNR regulates the site.

Source: NECSA

FIG. 3a. Vaalputs national radioactive waste disposal facility for low level radioactive waste disposal.

Spent fuel is stored on-site at Koeberg, most of it in wet storage in spent fuel pools, although some is stored on site in dry casks. The storage racks in the spent fuel pools were previously replaced with high density storage racks to allow for the storage of all spent fuel for the design life (40 years) of the station. Spent fuel from the SASARI-1 reactor is presently stored in a pipe store facility on the Pelindaba site.

Additional spent fuel storage capacity will be required due to a need to extend the operating lifetime of the two units at Koeberg from the current 40 years to a possible 60 years. To this end, Eskom is planning to construct an on-site Transient Interim Storage Facility (TISF) to increase the spent fuel dry storage capacity.

According to the Radioactive Waste Management Policy and Strategy for the Republic of South Africa [25], the storage of spent fuel on the reactor sites is finite and its practice unsustainable in the long term. With this in mind, NRWDI has begun plans to design, construct, commission, operate (including the licensing) of the Centralized Interim Storage Facility (CISF). The CISF is expected to come on-line in 2025.

Source: NECSA.

FIG. 3b. Dry and wet storage of spent nuclear fuel.

2.8. RESEARCH AND DEVELOPMENT

In general, research and development (R&D) in the nuclear energy field is performed mainly by Necsa, following the terms of the Nuclear Energy Act (1999) [18], which carries out a variety of R&D projects.

The South African Fundamental Atomic Research Installation (SAFARI-1) has played a pivotal role in Necsa’s attainment of global leadership in the production of radioisotopes, which are used in medical diagnoses and treatment, among other industrial applications. For more than 50 years multiple R&D publications have been generated within the Pelindaba complex, mainly as a result of the SAFARI-1 research reactor.

R&D for the long term management of South Africa’s radioactive waste is mandated to the NRWDI by the National Radioactive Waste Disposal Institute Act (Act No. 53 of 2008) [20] and relates to disposal processes and projects, for example, the siting, design, construction and operation of a deep geological repository for spent fuel and high level waste.

The Pebble Bed Modular Reactor (PBMR) project started as a research project by Eskom in 1993 and was formally established as a wholly owned Eskom subsidiary in 1999, known as Pebble Bed Modular Reactor Pty Ltd. The Nuclear Energy Policy of 2008 highlights the Government’s intention of pursuing a nationally developed PBMR programme.

In September 2010, the Cabinet approved that the PBMR be scaled down and put into a ‘care and maintenance’ mode to preserve and protect its intellectual property and assets. In October 2010, South Africa announced that it would not be in a position to commit to the Generation IV International Forum (GIF) very high temperature reactor (VHTR) systems agreement and hence withdrew its application. The PBMR also withdrew from the GIF VHTR materials project arrangement in November 2013. The country is still a GIF founding member as well as a signatory to the GIF charter.

South Africa is considering that Necsa carry out R&D on the small modular high temperature gas cooled reactor technology based on PBMR technology to determine whether this type of nuclear technology could be included in the energy supply system in the long term.

2.8.1. R&D organizations

R&D on accelerator based science is undertaken by iThemba Laboratory for Accelerator Based Sciences at the University of the Witwatersrand, as well as the iThemba Laboratory for Accelerator Based Sciences in the Western Cape. iThemba Labs is an entity of the National Research Fund which reports to the Ministry of Science and Innovation.

2.8.2. Development of advanced nuclear power technologies

Research is under way on the small modular high temperature gas cooled reactor technology based on PBMR technology to determine whether this type of nuclear technology could be included in the energy supply system in the future.

2.8.3. International cooperation and initiatives

South Africa participates actively in international cooperative endeavours regarding nuclear energy. The international cooperation is based on bilateral and multilateral agreements, international and regional programmes and projects, memorandums and commercial contracts.

South Africa is a member of the IAEA’s International Project on Innovative Nuclear Reactors and Fuel Cycles (INPRO). The Department of Mineral Resources and Energy is the implementing agent and a member of the INPRO Steering Committee.

South Africa is member of the Generation IV International Forum (GIF) although there are no registered project arrangements for South Africa. South Africa participates in structures of GIF, such as the Policy Group; Senior Industry Advisory Panel; Task Force on Research Infrastructures; Expert Group and Economic Modelling Working Group; Risk and Safety, Economic Modelling; and Proliferation Resistance and Physical Protection.

Through Eskom Holdings SOC, South Africa is a member of international organizations such as World Association of Nuclear Operators (WANO), World Nuclear Association (WNA) and Institute of Nuclear Power Operators (INPO).

2.9. HUMAN RESOURCES DEVELOPMENT

The country has been operating nuclear technology for over 50 years and the workforce is facing retirement from various installations. In an effort to ensure that there is an adequate skilled labour for the nuclear programme, the Government provides the following support:

The Skills Development Act, 1988 [26] encourages employers to invest in their employees by affording them the opportunity to learn at various learning institutions and by on-the-job training in order to improve their skills and by enabling activities for skills transfer from aging professionals to the young generation.

Necsa, which is responsible for nuclear research and development in the country, has a Learning Academy accredited as a Skill Development Provider and Trade Test Centre to provide for professional and technical skills.

Close cooperation between universities and research institutions provides for the postgraduate students with a financing scheme to conduct nuclear related research.

National Student Financial Aid Scheme provides financial aid to undergraduate students. The scope of nuclear courses is widening as most universities are currently introducing the subject in their academic programmes.

Bilateral agreements, in which students are afforded the opportunity to study and obtain international qualifications from other countries. The multilateral agreement with the IAEA creates a platform for both nuclear students and professionals and is an opportunity to interact with experienced nuclear personnel from other countries.

The Government has shown an interest to expand the country’s nuclear programme. This intent has culminated in the development of various working groups to address what will be the most important aspects to be put in place to ensure the readiness for such a programme. Human resource development is one of the aspects that is pivotal to address the adequate skilled workforce.

South Africa has leveraged on Nuclear Cooperation Agreements entered into with various vendor countries for the training of scientists and engineers in various aspects of the nuclear fuel cycle. As part of human resource development, students were sent to China, the Republic of Korea and the Russian Federation to pursue postgraduate studies in nuclear engineering.

2.10. STAKEHOLDER INVOLVEMENT

Guided by the Nuclear Communication Strategy [23], the Government collaborates on numerous stakeholder engagement platforms with nuclear industry partners to bring information on nuclear technology and energy to the public. The Strategy has classified various stakeholders and the means of engagement with them. The Strategy will be rolled out through a Communication Plan.

PSIFs are the platform for nuclear operators to provide the information about the safety of their operations to the communities residing close to nuclear facilities. PSIF meetings are conducted on a regular basis and facilitated by the National Nuclear Regulator.

In an effort to demystify nuclear energy, nuclear operators have visitor centres that receive the public on a daily basis to educate them about the peaceful applications of nuclear technology.

2.11. EMERGENCY PREPAREDNESS

In terms of Section 25 of the Disaster Management Act (DMA) of 2002 (Act No. 57 of 2002) [27], the Department of Minerals Resources and Energy (DMRE) is the national organ of State responsible for coordination and management of matters related to nuclear disaster management at national level. As a national organ of State, DMRE is required in terms of the DMA to develop and implement a national disaster management plan for nuclear emergencies.

The National Nuclear Disaster Management Plan (NNDMP) [28], as required by the DMA, was approved in 2005 and its primary purpose is to provide a national nuclear framework and outline the key functions, roles and responsibilities of the DMRE and relevant stakeholders in an effort to mitigate the consequences of radiological or nuclear emergencies. The NNDMP also provides for all relevant stakeholders to develop and align their plans to manage and mitigate against nuclear accidents.

Section 5(f) and Section 38 of the National Nuclear Regulator (NNR) of 1999 (Act No. 47 of 1999) [19] requires the NNR to ensure that emergency planning arrangements are in place and that emergency plans are developed and agreed upon by the authorization holder and the relevant municipalities and provincial authorities. The NNR must further ensure that such an emergency plan is effective for the protection of persons should a nuclear accident occur.

The effectiveness of the authorization holder’s integrated nuclear emergency plan is tested by means of conducting a regulatory emergency exercise. The regulatory emergency exercises are conducted on a two-year basis at nuclear installations, alternating between Koeberg NPP and Necsa. The exercise assesses the adequacy of the plan, preparedness and response arrangements, implementation of relevant procedures, equipment, resources, capabilities of personnel in performing their assigned tasks, ability of individuals and response organizations to work in a coordinated manner, and identification of areas of improvements in the existing emergency preparedness and response arrangements and capabilities. The NNR develops simulated scenarios in line with the set overall and specific objectives for the exercise.

When a nuclear accident occurs at a nuclear facility, the authorization holder will notify the local authorities and the NNR. The following stakeholders are assigned roles and responsibilities in case of a nuclear accident:

DMRE – deploys a representative to the local Disaster Management Centre to form part of a joint coordination and decision making team implementing the recommended protective actions. A DMRE representative is deployed to the National Disaster Management Centre to join the Disaster Coordination Team (DCT) to coordinate the resources at a national level in the implementation of the protective actions.

Authorization holders – responsible for managing the accident while it is still on-site and ensure that protective actions are implemented for the protection of people and the environment. Once the accident has an off-site impact, authorization holders are responsible for recommending protective actions to the local authorities.

Local authorities – responsible for implementation of the recommended protective actions once the decision is made by the DCT. In terms of the NNDMP, offsite nuclear accidents are declared as a ‘General Emergency’ in terms of Section 27 of the Disaster Management Act and such emergencies equate to a national state of disaster. The responsibility to declare a national state of disaster rests with the national Minister of Cooperative Governance and Traditional Affairs [27]. When a ‘General Emergency’ is declared, national resources will be made available to protect members of the public and the environment.

The Emergency Planning Steering and Oversight Committee (EPSOC) is established with the authorities in the vicinity of the nuclear installations for liaison on emergency preparedness, planning and response. This forum provides direction, steering and oversight relating to the development and implementation of emergency preparedness and response plans for Koeberg and Necsa. The committee meets on a quarterly basis and is chaired by a representative of the DMRE, which is the organ of State responsible for coordination of the National Nuclear Disaster Management Plan [28].

Section 37 of the NNR Act mandates the NNR with duties regarding nuclear accidents and incidents. In order to effectively fulfil this mandate, the NNR has established a Regulatory Emergency Response Centre (RERC) to coordinate the NNR response activities related to investigation of the cause, magnitude and impact of the emergency. The NNR Act is in the process of being updated with proposed additional responsibility that will include the involvement of the Regulator as an adviser to local authorities and the Minster of Mineral Resources and Energy in case of a nuclear or radiological emergency. Upon request, this responsibility will also include verification of protective actions for members of the public as recommended by the authorization holder [29]. The RERC will in future fulfil the proposed additional role of the NNR in emergency response.

In addition to the national arrangements to deal with a nuclear disaster, South Africa is a signatory to the IAEA Convention on Assistance in the Case of a Nuclear Accident or Radiological Emergency. The Convention sets out an international framework for co-operation between South Africa and the IAEA to facilitate prompt assistance and support in the event of nuclear accidents or radiological emergencies. During the emergency management process, Necsa, as a National Competent Authority, will notify the IAEA about the emergency. The NCA is responsible for requesting assistanceunder the relevant convention.

In terms of compensation of third parties in the case of nuclear damage, the operator has insured their facilities as required by Section 29 of the NNR Act.

3. NATIONAL LAWS AND REGULATIONS

3.1. REGULATORY FRAMEWORK

3.1.1. Regulatory authority(s)

Legislation on nuclear energy dates back to 1948 when the predecessor of the present South African Nuclear Energy Corporation (Necsa), namely the Atomic Energy Corporation (AEC), was created by the Atomic Energy Act. This act was amended over the years to keep pace with developments in nuclear energy. In 1963, the Nuclear Installations Act came into force. This made provision for the licensing of nuclear installations by the Atomic Energy Board.

The Uranium Enrichment Corporation was created in 1970 by the Uranium Enrichment Act. This allowed the enrichment of uranium by a State corporation separate from the Atomic Energy Board and subject to licensing by the latter. In 1982, the AEC was created and made responsible for all nuclear matters, including uranium enrichment. This came about through the Nuclear Energy Act of 1982. This act was amended several times in subsequent years. A major amendment in 1988 created the autonomous Council for Nuclear Safety (CNS), responsible for nuclear licensing and separate from the AEC (Nuclear Energy Amendment Act, Act No. 56 of 1988).

The old Nuclear Energy Act was replaced by a new act in 1993 (Nuclear Energy Act No. 131 of 1993). This maintained the autonomous character of the CNS but made provision for the implementation of a safeguards agreement with the IAEA pursuant to the requirements of the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons to which South Africa acceded in June 1991. This act has been superseded by two acts, the Nuclear Energy Act of 1999 [18] and the National Nuclear Regulator Act of 1999 [19].

The National Nuclear Regulator (NNR) is responsible for granting nuclear authorizations and exercising regulatory control related to safety over the siting, design, construction, operation, manufacture of component parts, and the decontamination, decommissioning and closure of nuclear installations; and vessels propelled by nuclear power or having radioactive material on board which is capable of causing nuclear damage.

The NNR, established as an independent juristic person by the NNR Act, comprises a Board of Directors, a CEO and staff. Its mandate and authority are conferred through sections 5 and 7 of the NNR Act, setting out the objectives and functions of the NNR.

The organizational structure of the NNR is depicted in Fig. 4 below.

Source: NNR

FIG. 4. NNR organizational structure.

The National Radioactive Waste Disposal Institute Act (NRWDIA) (Act No. 53 of 2008) [20] was proclaimed by the President of South Africa in Government Gazette No. 32764 and NRWDIA became effective on 1 December 2009. The NRWDIA endorsed the establishment of the National Radioactive Waste Disposal Institute (NRWDI).

Nuclear activities are also subject to numerous other pieces of legislation, for example, the Environmental Impact Assessment Regulations promulgated in 1997 by the terms of the Environment Conservation Act of 1989, and the disclosure of information by the terms of the Promotion of Access to Information Act of 2000.

The regulation of nuclear activities falls within the mandate of the NNR in accordance with the NNR Act, while environmental protection falls within the mandate of several government departments and organizations. The NNR has, as per the NNR Act Section 6, entered into cooperative agreements with several government organizations and departments on which functions are conferred in respect of the monitoring and control of radioactive material or exposure to ionizing radiation. This cooperation ensures the effective monitoring and control of the nuclear hazard, coordinates the exercise of such functions, minimizes the duplication of such functions and procedures regarding the exercise of such functions and promotes consistency in the exercise of such functions. The following Cooperative Agreements are in place between the NNR and other organs of State as far as protection from radiation hazards associated with nuclear power is concerned.

2007: The former Department of Environmental Affairs and Tourism (now Department of Forestry, Fisheries and the Environment (DFFE)), has responsibilities with regards to the regulation of environmental management associated with radiation hazards in terms of the National Environmental Management Act (Act No. 107 of 1998) [31] and Environment Conservation Act (Act No. 73 of 1989) [32].

2007: The South African Maritime Safety Authority (SAMSA) has responsibilities with regard to radiation hazards in terms of the South African Maritime Safety Authority Act (Act No. 5 of 1998) [33] and related legislation.

2007: The Department of Transport has responsibilities with regard to road safety and the regulation of the transportation of any prescribed dangerous goods in terms of the National Road Traffic Act (Act No. 93 of 1996) [34].

2007: The Department of Health (Directorate Radiation Control) has responsibilities with regard to the regulation of radiation hazards in terms of the Hazardous Substance Act (Act No. 15 of 1972) [35].

2007: The former Department of Water Affairs and Forestry (now Human Settlements, Water and Sanitation) has responsibilities with regard to the regulation of the sources of radiation hazards that may impact on water resources, as well as to manage the water resources of the Republic of South Africa, and in terms of the National Water Act (Act No. 36 of 1998) [36].

2007: The former Department of Minerals and Energy-Electricity and Nuclear (now Department of Mineral Resources and Energy – Nuclear), in servicing the obligations of the Minister of Mineral Resources and Energy in terms of the Nuclear Energy Act (Act No. 46 of 1999) and the National Nuclear Regulator Act (Act No. 47 of 1999), has functions in respect of the monitoring and control of radiation material or exposure to ionizing radiation.

2007: The former Department of Labour (now Employment and Labour) has responsibilities with regard to the regulation of all work related hazards with the exception of ionizing radiation hazard in terms of the Occupational Health and Safety Act (Act No. 85 of 1993) [37].

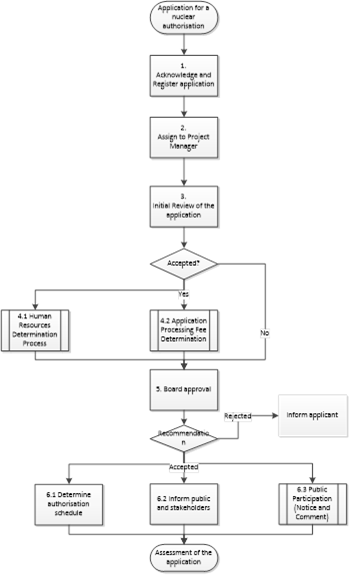

3.1.2. Licensing process

The nuclear authorization process is outlined in Chapter 3 of the NNR Act. It is stated in the NNR Act that no person may site, construct, operate, decontaminate or decommission a nuclear installation, except under the authority of a Nuclear Installation Licence (NIL). The Act makes provision for the following:

Application for a nuclear installation;

Exemptions for certain actions;

Conditions related to NIL;

Responsibilities of holders of nuclear authorizations;

Revocation and surrender of nuclear authorizations;

Fees for nuclear authorizations.

The Act empowers the NNR to grant or refuse a licence; to change a licence at the request of the licence holder, to change a licence at the request of NNR; and to surrender or revoke a licence.

A nuclear authorization is the process of granting a written approval by the National Nuclear Regulator to applicants and/or operating organizations to perform nuclear related activities as detailed in the scope of authorization. The authorization process involves receiving, reviewing and approval of authorization requests from applicants and/or authorization holders. The NNR Act makes provision for the granting of four categories of nuclear authorization. These are:

Nuclear Installation Licences,

Nuclear Vessel Licences,

Certificates of Registration, and

Certificates of Exemption.

The right to appeal against decisions of the NNR, the NNR Board of the NNR and the Minister is outlined in the NNR Act Chapter 6.

The NNR Act, Section 36, also empowers the Minister, on the recommendation of the Board, to make regulations regarding safety standards and regulatory practices. The regulations are mandatory and set down specific requirements to be upheld by the authorization holder or an applicant for a nuclear authorization. The NNR also established regulatory guidance documents aimed at expanding its position and clarity of the requirements as prescribed in the NNR Act and Regulations. The NNR further developed process documents aimed at guiding its staff members on the authorization process. These documents include:

POL-REG-001 – Regulatory Philosophy and Policy of the NNR

PRO-AUT-01 – Nuclear Authorization Process (see Figure 5)

Prior to the granting of an authorization, the applicant is required to apply to the NNR, in the prescribed format, detailing the intended activities and providing a demonstration of safety and compliance to the NNR requirements. The documentation submitted must address licensing aspects in the design of any facilities concerned and safety in the way the facility will be constructed, commissioned, operated, maintained and decommissioned.

The authorization conditions represent a framework within which the applicant or holder of the nuclear authorization is obliged to comply with particular requirements in respect of design, operation, maintenance and decommissioning. The conditions of authorization also oblige the holder of the authorization to provide a demonstration of compliance through the submission of routine and non-routine reports.

FIG. 5. Application process for a nuclear authorization.

Some of the standard conditions included in a nuclear authorization address:

The description and configuration of the authorized facility or action;

Requirements in respect of modification to facilities;

Operational requirements in the form of operating technical specifications, procedures or programmes as appropriate;

Maintenance testing and inspection requirements;

Operational radiation protection programmes;

Radioactive waste management programmes;

Emergency planning and preparedness requirements as appropriate;

Physical security;

Transport of radioactive material;

Public exposure safety assessments;

Quality assurance.

The current licensing basis for NPPs refers to the safety case that is applicable at any stage during the lifetime of the plant. The current licensing basis includes the Safety Analysis Report (SAR), General Operating Rules (GOR), nuclear safety requirements, the principal safety documentation that demonstrates compliance with these requirements, and all licence-binding documentation. The current licensing basis constitutes the basis for the safe operation of NPPs and the issuance of the Koeberg Nuclear Installation Licence.

In order for the NNR to grant a licence to operate the Koeberg NPP, the following principles amongst others must be applied for all activities that have an impact on nuclear safety and these include:

Accident prevention and mitigation;

Optimization of protection and safety;

Fundamental safety criteria;

Safety culture;

Defence-in-depth;

ALARA;

Good engineering practice;

Quality management;

Accident management and emergency preparedness;

Graded approach.

Source: Eskom

FIG. 6. Koeberg spent fuel pool.

Regulatory Framework for Nuclear Licence Extension

The nuclear licence extension is outlined in the Regulations on the Long Term Operation of Nuclear Installations No. R266 dated 26 March 2021 (LTO Regulations) [38]. These regulations are established in terms of section 36 read with section 47 of the NNR Act. Furthermore, the NNR developed regulatory guidance with details on how to apply for a nuclear licence extension.

As in the case of the initial nuclear licence application, the applicant is required to lodge the application to operate a nuclear installation beyond its established time frame to the CEO of the NNR, as per the format prescribed in Regulations GN No. 1219 [45]. The applicant for licence extension is required to submit a safety case to the NNR, and below is the summary of the key requirements:

Demonstrate compliance with regulatory safety criteria and requirements;

Prepare safety analyses and consider ageing of structures, systems and components;

Overall safety assessment of the nuclear installation for the intended period of LTO;

Demonstrate financial and human resources for the LTO;

Identify safety improvements of the installation in order to validate the licensing basis for the LTO period.

Regulation 5 of the LTO Regulations prescribe the factors the regulator needs to consider in evaluating the application for LTO. These include the establishment of the safety related programmes for safety, ageing management programme, time limited aging analyses and periodic safety review in order to justify the LTO programme. Regulation 6 prescribes the requirements of the programme for LTO. Furthermore, the NNR will, after assessing the licence application documentation, determine the period of the licence beyond the established timeframe. Regulation 8 outlines legal controls such as offences and penalties to the entities that may operate their nuclear installations beyond the stipulated period of the issued licence.

The NNR is committed to conducting its regulatory responsibilities in an open and transparent manner and keeping the public informed of its oversight activities. The public’s interest in the fair regulation of nuclear activities is being recognized and opportunities for concerned citizens inputs are provided. The NNR considers public hearings a valued and important part of the licensing process and encourages the public’s participation and involvement.

3.2. NATIONAL LAWS AND REGULATIONS IN NUCLEAR POWER

| Legislation | Date | Reference No. |

| Nuclear Energy Policy for the Republic of South Africa | 2008 | [4] |

| Nuclear Energy Act, 1999 (Act No. 46 of 1999) | 1999 | [18] |

| National Nuclear Regulator Act, 1999 (Act No. 47 of 1999) | 1999 | [19] |

| The National Radioactive Waste Disposal Institute Act, 2008 (Act No. 58 of 2008) | 2008 | [20] |

| Disaster Management Act (DMA) of 2002 (Act No. 57 of 2002) | 2002 | [27] |

| National Key Points Act No. 102 of 1980 | 1980 | [39] |

| National Strategic Intelligence Act No. 39 of 1994 | 1984 | [40] |

| Minimum Information Security Standards (1996) | 1996 | [41] |

| Protection of Information Act (Act No. 84 of 1982) | 1982 | [42] |

| Protection of Constitutional Democracy Against Terrorist and Related Activities Act (Act No. 33 of 2004) | 2004 | [43] |

| Critical Infrastructure Protection Act (Act No. 8 of 2019) | 2019 | [44] |

| National Water Act, 1998 (Act No. 36 of 1998) | 1998 | [36] |

| National Environmental Management Act, 1998 (Act No. 107 of 1998) | 1998 | [31] |

| National Road Traffic Act (Act No. 93 of 1996) | 1996 | [34] |

| Environment Conservation Act (Act No. 73 of 1989) | 1989 | [32] |

| Hazardous Substance Act (Act No. 15 of 1972) | 1972 | [35] |

| Regulations | Date | Reference No. |

| Safety Standards and Regulatory Practices (SSRP, No R388) | 2006 | [46] |

| Licensing of Sites for New Nuclear Installations (R927) | 2011 | [47] |

| Long Term Operations for Nuclear Installations (R266) | 2021 | [48] |

REFERENCES

IAEA Power Reactor Information System (PRIS) Database, https://pris.iaea.org/PRIS/CountryStatistics/CountryDetails.aspx?current=ZA

White Paper on the Energy Policy of the Republic of South Africa, December 1998, http://www.energy.gov.za/files/policies/whitepaper_energypolicy_1998.pdf

White Paper on Renewable Energy, November 2003, http://www.energy.gov.za/files/policies/whitepaper_renewables_2003.pdf

Nuclear Energy Policy for the Republic of South Africa, June 2008, http://www.energy.gov.za/files/policies/policy_nuclear_energy_2008.pdf

National Development Plan 2030, https://www.nationalplanningcommission.org.za/assets/Documents/ndp-2030-our-future-make-it-work.pdf

Integrated Resources Plan for Electricity, October 2010, http://www.energy.gov.za/IRP/irp%20files/INTEGRATED_RESOURCES_PLAN_ELECTRICITY_2010_v8.pdf

Integrated Resources Plan (IRP 2019),

National Energy Efficiency Strategy,

https://www.gov.za/sites/default/files/gcis_document/201409/32249580.pdf

Post-2015 National Energy Efficiency Strategy, September 2016, http://www.energy.gov.za/files/policies/Draft-Post-2015-2030-National-Energy-Efficiency-Strategy.pdf

South African National Standard, Energy Management Systems – Requirements with Guidance for Use, SANS 50001:2011, https://store.sabs.co.za/pdfpreview.php?hash=77a66e5dffcd80c6cffecb1893c5c83932213038&preview=yes

South African National Standard, Measurement and Verification of Energy and Demand Savings, SANS 50010:2018, https://store.sabs.co.za/pdfpreview.php?hash=1e7bd3843baab4644997f2a5fb715a527d450d48&preview=yes

National Energy Act 2008, Published for Public Comment: Draft Regulations Regarding Registration, Reporting on Energy Management and Submission of Energy Management Plans, No.R.259, March 2015,

National Energy Regulator Act, 2004 (Act No. 40 of 2004), http://www.energy.gov.za/files/policies/National%20Energy%20Regulator%20Act%2040%20of%202004.pdf

Electricity Regulation Act, 2006 (Act No. 4 of 2006), http://www.energy.gov.za/files/policies/ELECTRICITY%20REGULATION%20ACT%204%20OF%202006.pdf

Gas Act, 2001 (Act No. 48 of 2001), http://www.energy.gov.za/files/policies/act_gas_48of2001_national_2002

Petroleum Pipelines Act, 2003 (Act No. 60 of 2003), https://www.gov.za/sites/default/files/gcis_document/201409/a60-03.pdf

Eskom Integrated Report, 31 March 2020

https://www.eskom.co.za/IR2020/Documents/Eskom%202020%20integrated%report_secured.pdf

Nuclear Energy Act, 1999 (Act No. 46 of 1999), http://www.energy.gov.za/files/policies/act_nuclear_46_1999.pdf

National Nuclear Regulator Act, 1999 (Act No. 47 of 1999), http://www.energy.gov.za/files/policies/act_nuclear_47_1999A.pdf

The National Radioactive Waste Disposal Institute Act, 2008 (Act No. 58 of 2008) http://www.energy.gov.za/files/policies/act_nuclear_53_2008_NatRadioActWaste.pdf

Heart of the Matter: Nuclear Attitudes in South Africa,

http://www.hsrc.ac.za/en/review/june-2012/heart-of-the-matter-nuclear-attitudes-in-south-africa

Public Perceptions of Nuclear Science in South Africa, 2013 Tabulation Report, www.hsrc.ac.za/en/research-outputs/ktree-doc/13832

Nuclear Communication Strategy

NNR Regulations No. R.388 on Safety Standards and Regulatory Practices, 28 April 2006, http://www.nnr.co.za/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/No-388-NNR-Regulation-on-Safety-Standards-and-Regulatory-Practices.pdf

Radioactive Waste Management Policy and Strategy for the Republic of South Africa 2005, https://www.nrwdi.org.za/file/Radwaste%20Policy%20and%20Strategy%20Sep%202009.pdf

Skills Development Act, 1988, https://www.gov.za/sites/default/files/gcis_document/201409/a97-98.pdf

Disaster Management Act, 2002 (Act No. 57 of 2002), https://www.gov.za/sites/default/files/gcis_document/201409/a57-020.pdf

National Nuclear Disaster Management Plan, Rev 0, October 2005, https://www.gov.za/sites/default/files/gcis_document/201409/dmenucleardisaster05oct20050.pdf

PRC-RERC-05, NNR Response to Notification of Nuclear or Radiological Emergencies

8th National Report by South Africa on the Convention on Nuclear Safety

National Environmental Management Act, 1998 (Act No. 107 of 1998)

https://www.gov.za/sites/default/files/gcis_document/201409/a107-98.pdf

Environment Conservation Act, 1989 (Act No. 73 of 1989)

https://www.gov.za/sites/default/files/gcis_document/201503/act-73-1989.pdf

South African Maritime Safety Authority Act, 1998 (Act No. 5 of 1998),

https://www.gov.za/sites/default/files/gcis_document/201409/a5-98.pdf

National Road Traffic Act, 1996 (Act No. 93 of 1996)

https://www.gov.za/sites/default/files/gcis_document/201409/act93of1996.pdf

Hazardous Substances Act, 1973 (Act No. 15 of 1973)

https://www.gov.za/sites/default/files/gcis_document/201504/act-15-1973.pdf

National Water Act, 1998 (Act No. 36 of 1998)

https://www.gov.za/sites/default/files/gcis_document/201409/a36-98.pdf

Occupational Health and Safety Act, (Act No. 85 of 1993)

https://www.gov.za/sites/default/files/gcis_document/201409/act85of1993.pdf

Regulations on the Long Term Operation of Nuclear Installations No. R266 dated 26 March 2021

National Key Points Act, 1980 (Act No. 102 of 1980)

https://www.gov.za/sites/default/files/gcis_document/201503/act-102-1980.pdf

National Strategic Intelligence Act, 1994 (Act No. 39 of 1994)

https://www.gov.za/sites/default/files/gcis_document/201409/act39of1994.pdf

Minimum Information Security Standards, 1996

Protection of Information Act, 1982 (Act No. 84 of 1982)

https://www.gov.za/sites/default/files/gcis_document/201503/act-84-1982.pdf

Protection of Constitutional Democracy Against Terrorist and Related Activities Act, 2004 (Act No. 33 of 2004)

https://www.gov.za/sites/default/files/gcis_document/201409/a33-04.pdf

Critical Infrastructure Protection Act, 2019 (Act No. 8 of 2019)

Format for the Application for a Nuclear Installation License or a Certificate of Registration or a Certificate of Exemption, GN 1219, 21 December 2007

Safety Standards and Regulatory Practices (SSRP, No R388)

Licensing of Sites for New Nuclear Installations (R927)

Long Term Operations for Nuclear Installations (R266)

https://nnr.co.za/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/Regulations-on-LTO-of-nuclear-installations.pdf

8th National Report by South Africa on the Convention on Nuclear Safety, 2019,

South African National Report on the Compliance to Obligations under the Joint Convention of Safety of Spent Fuel Management and on the Safety of Radioactive Management, 2020,

PRC-RERC-04 RERC Emergency Preparedness and Response Plan

APPENDIX 1. INTERNATIONAL, MULTILATERAL AND BILATERAL AGREEMENTS

| AGREEMENTS WITH THE IAEA | ||

| NPT related agreement INFCIRC/394 | Entry into force: | 16 September 1991 |

| Additional Protocol | Entry into force: | 13 September 2002 |

| Improved procedures for designation of safeguards inspectors | Accepted | 19 July 1995 |

| Supplementary Agreement on Provision of Technical Assistance by the IAEA | Entry into force: | |

| African Regional Cooperative Agreement for Research, Development and Training Related to Nuclear Science and Technology (AFRA) | Entry into force: | 18 May 1992 |